Recognizing Laryngeal Paralysis (Lar Par) in Your Dog

Recognizing Laryngeal Paralysis (Lar Par) in Your Dog

Today’s blogpost is inspired by four recent patients with a shared condition: laryngeal paralysis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “lar par.” Many pet owners are not familiar with laryngeal paralysis, so I will explain this disorder by discussing the role of the larynx in dogs, these patients’ clinical signs, their risk factors and possible outcomes.

Laryngeal Function in Dogs

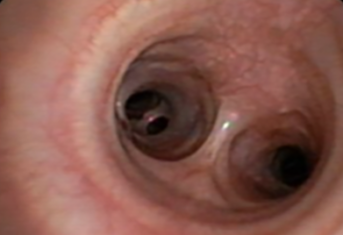

The larynx is a complex organ involved in two critical canine functions – barking and protecting the lungs from food and water going “down the wrong pipe.” The larynx sits just in front of the windpipe, or trachea. When the larynx opens, breathing occurs and barking can happen. When your dog swallows, the larynx closes, directing food and water into the esophagus and stomach and preventing food and water from going into the trachea and lungs.

The larynx has a double closure, kind of like a watertight double zipper plastic bag. The epiglottis, a flap of cartilage, forms part one of the closure. The left and right arytenoid cartilages form part two of the closure.

Laryngeal Dysfunction in Dogs

Even if you’ve never heard of laryngeal paralysis, you will easily recognize the clinical signs of a larynx that is no longer working well – drastic changes in your dog’s bark. The family of one of the lar par dogs seen at AMC reported their dog could no longer bark, and another family noted their dog’s voice had changed. Since the larynx is responsible for a dog’s “voice,” these details are not surprising. All of these patients had the noisy breathing characteristic of laryngeal paralysis. All four of these dogs were admitted to AMC suffering from pneumonia and in respiratory distress. Given that one of the larynx’s jobs is to protect the lungs from food and water, when the larynx doesn’t work, food and water get into the lungs setting off aspiration pneumonia.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Laryngeal Paralysis in Dogs

Laryngeal paralysis is not hard to diagnose in dogs with the telltale signs noted above: voice changes, noisy breathing and pneumonia. To diagnose lar par and develop a treatment protocol, AMC’s Internal Medicine specialists will perform a sedated laryngeal exam where they watch the movement (or decreased movement) of the arytenoid cartilages. For some dogs, weight loss, a cool environment, sedation and limited exercise during hot weather are enough to mitigate the clinical signs of laryngeal paralysis. In severe cases, AMC’s board-certified surgeons will surgically suture the larynx open. This surgery improves respiration, but the risk of aspiration pneumonia persists.

The outcome for dogs with laryngeal paralysis is mixed. Some recover from aspiration pneumonia while it can be a constant challenge for others.

Risk Factors for Laryngeal Paralysis in Dogs

The four lar par dogs discussed here have some features in common, and these similarities are not surprising because they are typical risk factors for laryngeal paralysis. First, all four dogs weighed 60+ pounds. Laryngeal paralysis occurs most commonly in large breed dogs. This quartet included a Labrador retriever, a pit bull, a standard poodle and a German shepherd mix. All four were admitted to AMC between May and September, New York City’s hottest months. Dogs cool themselves by panting, and a dog with a paralyzed larynx cannot pant effectively and are prone to overheating. If you have a large breed dog, especially one of advanced age, be mindful of overexertion and the risk of lar par during hot summer months.

Owners of small breed dogs should be aware of another respiratory condition exacerbated by hot summer weather: tracheal collapse. Read more about tracheal collapse in our Pet Health Library.