Everyday Medicine: Packed Cell Volume

Everyday Medicine: Packed Cell Volume

“Everyday Medicine” is an intermittent series of blog posts highlighting tests, treatments, and procedures common in daily Animal Medical Center practice. Some past examples of this type of blog post include “Cytology” and “Blood Pressure.” Today’s post focuses on packed cell volume.

What is Packed Cell Volume?

Despite the fact that a packed cell volume is measured dozens of times a day at the Animal Medical Center, most pet owners have never heard of packed cell volume, sometimes referred to as a hematocrit. If one of your pets has experienced a serious issue with anemia, then you might have heard your veterinarian talk about this test. Also known as PCV, packed cell volume is one measure of the number of red blood cells in the blood. There are other methods to assess the number of red blood cells, but these take more time and much more sophisticated laboratory equipment. The laboratory can count the number of red blood cells; there are millions in a drop of blood. The oxygen-carrying protein hemoglobin contained inside of red blood cells can also be measured; like red blood cells, hemoglobin decreases when a patient is anemic.

How is PCV Measured?

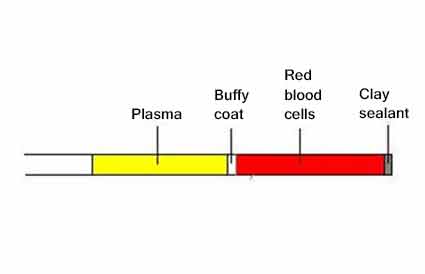

First, a blood sample is collected from the patient, typically about ½ teaspoon. Some of the sample is sent to the lab, but a drop or two is placed into a very thin glass tube called a capillary tube. One end of the tube is filled with a soft clay which acts as a stopper to keep the blood in the tube. The tube is placed in the centrifuge and in just a couple of minutes, the centrifugal force “packs” the red blood cells in the bottom of the tube and leaves the clear plasma above. The PCV is the volume percentage composed of red blood cells in the tube. In a normal dog or cat, the PCV is 35-50%.

But Wait, There’s More to a PCV Than Red Blood Cells

The remainder of the volume in the capillary tube is a few percentages of white blood cells and platelets in a section called the buffy coat. A bit more than half of the tube is plasma, or the liquid component of blood. The PCV not only gives a clue to anemia but if the percentage of plasma decreases, dehydration may be part of the diagnosis. In a normal patient, plasma is clear. If plasma is bright yellow, that signifies jaundice and testing of the liver will be necessary. The capillary tube can be snapped open and the plasma put on a handheld device that will measure the protein level of the blood. High protein indicates dehydration; low protein suggests there is protein loss or severe malnutrition. If the percentage of white blood cells increases, then veterinarians worry about infection or leukemia.

When Do Veterinarians Use a PCV?

Because a PCV gives information about anemia, blood protein and hydration status, nearly every patient coming to an animal ER has a PCV obtained. A PCV is a common preoperative test because a PCV is quick and easy. The small volume of blood required for a PCV means the test can be repeated in the operating room without taking excessive amounts of blood from the patient. Any veterinarian monitoring a patient with anemia may rely on a PCV for quick assessment of the patient’s status.

Given its simplicity, speed with which the results are available and the helpful information obtained, the packed cell volume is clearly an everyday test.