Leeches, bloodletting, and phlebotomy in the 21st century

Leeches, bloodletting, and phlebotomy in the 21st century

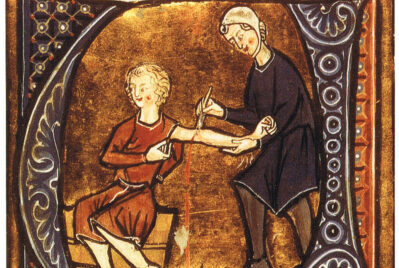

Starting with the ancient Egyptians and continuing through the 19th century, bloodletting – the therapeutic removal of blood from the body – was a commonly practiced medical procedure. According to Hippocrates, illness was caused by an imbalance of the four basic humors: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. Procedures such as bloodletting, purging, catharsis and diuresis restored that balance. During medieval times, bloodletting was accomplished using special instruments known as lancets and fleams. Alternatively, medical leeches, Hirudo medicinalis, were deployed as bloodletters. Bloodletting could easily get out of hand and has long thought to have been a major contributing factor to the death of our first president, George Washington.

Surely in the 21st century we have better treatments for our pets? Believe it or not, modern medicine has vindicated bloodletting as a medically beneficial treatment in a handful of instances.

Too much blood

Rosie, one of my grey muzzle patients, made a visit to AMC’s Neurology Service for not being quite right. The neurologic examination was not conclusive, and an MRI was recommended. Rosie came to see me for a pre-MRI examination. I was surprised to find her red blood cell count elevated, explaining why she was not acting quite right. When red bloods cells increase, the blood becomes very thick. Thick blood cannot deliver oxygen through small blood vessels like those in the brain. After a battery of tests, I determined she had a bone marrow disorder called primary polycythemia. The quick fix for this disease is phlebotomy, or the withdrawal of about 1 tablespoon of blood per kilogram of body weight. Phlebotomy may be followed by treatment with an oral medication to keep the red blood cell count at a normal level. The use of medical leeches has also been described for treatment of this disorder in a cat, with one leech being able to remove 2 teaspoons of blood.

Low oxygen results in high red blood cells

About the same time I was evaluating Rosie, AMC’s Cardiology Service was evaluating a kitten with a birth defect in his heart. In this disorder, the abnormal structure of the heart allows oxygenated blood to mix with unoxygenated blood. The mixture does not deliver enough oxygen to the body’s organs. The oxygen deficiency cranks up red blood cell production to supranormal levels to compensate for low oxygen. Unlike Rosie, this kitten’s problem was his heart, not his bone marrow; however, the impact of thick blood on delivery to small blood vessels was the same. Her cardiologists are monitoring her closely in case he too needs phlebotomy to control clinical signs associated with polycythemia.

Will my doctor prescribe bloodletting for me?

A few rare disorders in people are still treated with bloodletting. Primary polycythemia occurs in people as well as in dogs and might be treated with phlebotomy. Some disorders of iron metabolism are treated by intermittent phlebotomy to control the iron levels in the body. As for leeches, they are making a 21st century comeback as an invaluable medical device in reconstructive microsurgery. No longer medieval, bloodletting is very 21st century.